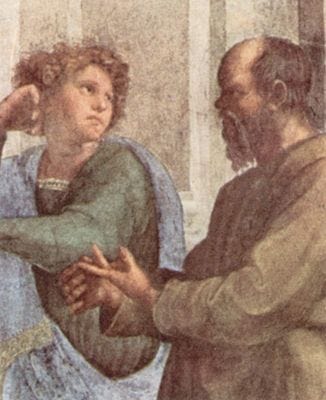

In one of Plato’s dialogues, the Charmides, Socrates and company get themselves into a state of dizzying perplexity over the very idea of self-knowledge. They end up finding it so paradoxical that they begin to despair of its possibility altogether. Well, what’s so perplexing about self-knowledge?

In fact, the dialogue is not, in the first instance, about self-knowledge at all, but about what is called, in Greek, sōphrosunē—“temperance” or “moderation,” as it is usually translated, but sōphrosunē is in fact one of those Greek words that have no real equivalent in English.1 And if we translate sōphrosunē as “temperance” we are likely to be puzzled by the fact that the discussion ends up focusing almost entirely on self-knowledge. Why should one need any special degree of self-knowledge in order to be temperate?

I’ve come to think that something like “self-possession” better captures what Plato was concerned with. It retains an important connection with the virtue of temperance, as in the traditional translation, since it is especially important—and difficult—to remain in possession of yourself (your senses, your values) in the face of temptation; but it helps us to understand why sōphrosunē was so absolutely central to the Greeks. —Of course, moralists are prone to obsess over temperance, and to suppose that “being good” is all about resisting temptation. (We might think of this as the “being good means being a good boy” conception of morality.) But this flattens our ethical lives in a way that is foreign to Greek thought. Their morality was never so puritanical as all that.

In any case, aside from what the Greeks may have thought of the matter, it does seem right that something like self-possession, or (as we might also call it) integrity, should be the key to an ethical life. And if we take self-possession (rather than temperance) to be the main object of inquiry in Charmides, then it’s easy to see how Socrates and company end up getting mired in the puzzles surrounding self-knowledge: to be self-possessed you will certainly need to know who you are—above all, to know where you stand and what you stand for.

But, even so, the course of their discussion is baffling—baffling to them, certainly, but baffling in another way for us, Plato’s readers. The set-up primes us to be thinking of the ethical difficulties that attach to knowing yourself. What stands in the way of the kind of self-knowledge required for integrity is often something like a failure of courage: the courage to be entirely honest with yourself, to refuse to succumb to wishful thinking. (I’ll come back to that.) But the difficulties Socrates and company end up considering are, instead, rather of an abstract and conceptual nature. Here are a couple of them, just for kicks:

Different kinds of knowledge are distinguished by their objects, by what they are knowledge of: mathematics concerns mathematical objects (numbers, figures, and so on); carpentry (Plato was always happy to count carpentry as a type of knowledge) concerns the construction of wooden structures; and political science concerns political institutions (or it would if it were actually a form of knowledge); and so on. But if there is a form of knowledge that could be reasonably called self-knowledge, what would its object be? According to Socrates and his increasingly pliant interlocutor, at any rate, it would have to be knowledge of knowledge itself. What would it mean to possess such a knowledge? Apparently, being able to know whether or not you possess other forms of knowledge. But (and here the real difficulties begin) in order to know whether you know (for instance) geometry, you’d have to know...geometry! (After all, how could I tell whether my beliefs about geometrical figures were mere beliefs or genuine knowledge unless I had some knowledge of geometry?) And now it sounds like a general capacity for self-knowledge is impossible (it would have to involve the possession of all other forms of knowledge) and anyway useless (since, if you had genuine knowledge of geometry, you would know that you did).

Consider the fact the eye cannot see itself. This doesn’t seem to be a contingent fact, owing to the limitations of human vision. There is some impossibility in the very idea of a perceptual organ perceiving itself directly—the thing doing the seeing cannot be in its own field of vision. (One part of a sensory organ can sense another part of that same sensory organ, e.g., the skin, but this is no counterexample.) So, too, we should expect that the faculty of knowing cannot be known by itself.

These are interesting intellectual puzzles, and I begrudge no one the giddily vertiginous joys that attend probing the paradoxes of self-reference. But they seem to involve a typically Socratic sleight of hand. “What is self-knowledge?” You expect something like: “Knowledge of the self that you are”—for instance, knowledge of your character, or knowledge of your deepest desires and aspirations. But this is not what at all what we find in the Charmides. Instead, Socrates takes self-knowledge to be the knowledge of knowledge itself: a kind of science of sciences. We have moved far indeed from the concern with moral integrity that set us on this path.

Socrates’ arguments lead to a dead end, and I’ll leave the task of sorting out just where they go wrong as a diversion for the reader’s leisure. If we want to understand why self-knowledge is difficult, we must look elsewhere. Let’s begin, not with abstract intellectual puzzles, but with—as Plato’s great student, Aristotle, would say—the phenomena.

As I’ve gotten older (as I keep doing, indefatigably), I’ve come to see that underlying all the decisions that I’ve come to regret—wrong turns and wrongdoings—was some failure of self-knowledge. There was always something I couldn’t, or wouldn’t, admit to myself: what I really wanted, or what I really cared about, or who I really was. One thing that makes such failures of self-knowledge peculiar is this: Afterwards, when you’ve come to your senses, you always think: “But on some level I did know!” or “I must (deep down) have known”—for instance, “that I would never be happy as a lawyer,” or “that I never really loved her.” You think, with a pained exasperation, “How could I have been so foolish?” “How so blind?”

Now, to some degree, this is likely an illusion. But not always and not entirely. And it illustrates what makes self-knowledge genuinely puzzling. Often when you fail to know something, it’s simply that you lacked some crucial piece of evidence. You might chastise yourself for failing to look more carefully for or at the evidence, but that’s something altogether different from what stands in the way of self-knowledge. In that case, the evidence is all in front of you; no one could be better positioned or have more information relevant to the matter. Nothing was hidden—or, if something was, it had to be you doing the hiding.

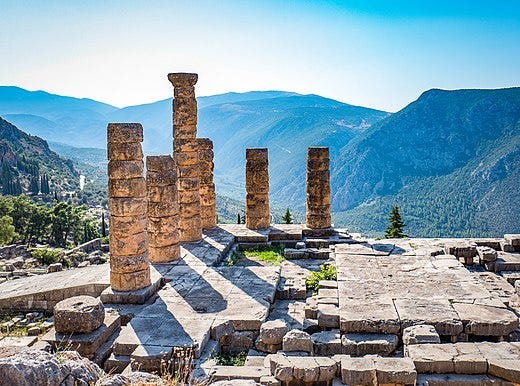

“No one could be better positioned or have more information relevant to the matter.” So it would seem, and yet so often it is others who see us first and most clearly. The author (traditionally thought to be Aristotle) of an ancient text on ethics called the Magna Moralia put it this way:

People are not able to observe themselves by themselves. That they cannot is clear from the way we censure others without noticing that we do the same things ourselves; and this comes about through partiality or passion—for many of us, these things obscure correct judgment.

Partiality and passion obscure us from ourselves. But not, I suppose, as the clouds obscure the moon. Intense passion can muddle your mind—if you are newly smitten, then you might find it difficult to follow a geometrical proof—but this is not the sense, I don’t think, in which it interferes with self-knowledge. Rather, our pride makes it difficult to be honest with ourselves. It is, well, nice to think that you are a morally decent, intelligent, capable person, and this can lead in obvious ways to a kind of self-imposed blindness. (We might add that the opposite sometimes happens as well: There are those who are blind to their own virtues, who are much more charitable in their “readings” of others than of themselves.)

Philosophers and psychologists speak sometimes of “motivated reasoning.” Motivated reasoning is what occurs when you want the inquiry to turn out one way rather than another and this desire somehow influences the conclusion that you come to. You ignore evidence because you want things to be otherwise than the evidence suggests. It seems to me that failures of self-knowledge must necessarily be “motivated” in this sense. You can’t simply fail to know yourself; you must somehow hide the evidence from yourself.

This suggests that self-knowledge is paradoxical because its contrary is not self-ignorance but self-deception—and self-deception is paradoxical. Ordinarily we think of deception as getting someone to believe something that you know to be false. But it is hard to see how you could play such tricks on yourself. After all, to do so you need to both know that the belief in question is false, and yet nonetheless manage to get yourself to believe it.

(You might simply deny that self-deception is genuinely a species of deception at all. But I, like the ordinary language philosophers of yore, have a kind of faith that there is a wisdom contained in the words we use—a kind of communal logic to ordinary usage, much more intelligent that any of us individually are or could be. The fact that we speak of self-deception, and manage to understand each other, has something to teach us both about the nature of the self and the nature of deception.)

So, how do we pull it off, and so often? I don’t think it’s quite right to say, flatly, that it is because we are blinded by egoism. That’s not quite wrong either, of course, but it’s not the whole story, and anyway it doesn’t enable us to understand how we manage to do this paradoxical thing. I think it has to do with the fact that the self one is trying (and in this case failing) to know or understand is always partly an aspiration, and not entirely an antecedently given fact.

Consider the fact that we often come to know ourselves only in relation to others. In the course of a conversation with a friend, I come—falteringly perhaps—to recognize what I really believe, for instance, or what I really value. That is to say, I come to determine what I believe or value. This is not like determining the length of a table, which had a determinate length before I went and got the ruler, and I am simply trying to figure out what that length is. When I determine what I value, by contrast, I am not (exactly?) discovering something that was already the case; I am determining what I believe in the sense of rendering my beliefs more determinate. The process of coming to know myself is often the process of coming to constitute myself. To some degree, I decide who I am.

This is not to say that anything goes, that whatever I decide will be ipso facto true. We can be wrong, as we often are. But, even if all the evidence points the other way, still it could be true that I am honest, intelligent, capable, or that I possess whatever particular virtue I might hope to. I really could (deep down) be some way, even though from the outside it looks for all the world like I am not, because I really might have it in me to become thus. In a given case this may be highly improbable, but it is after all possible. And this, in a fairly evident way, opens up a lot of space for fantasy and wishful thinking.

Earlier, I set aside the merely conceptual puzzles about self-knowledge that animate Plato’s Charmides; they didn’t seem especially pertinent to the ethical issues surrounding self-knowledge that I wanted to take up. But now perhaps in a sense I’ve found my way back to the fundamental conceptual issue after all. It is part of the concepts of “inquiry” and “truth” that, if I’m inquiring into whether something is true, it cannot be that it is made true by the inquiry itself, or by my coming to believe it. But now it looks like this sort of independence of what is known from the process of knowing fails in the case of self-knowledge. The self that you are seeking to know is re-shaped by your very epistemic efforts. And this, in a certain philosophical mood anyway, can trouble our conviction that it really makes sense to speak of self-knowledge at all. And yet it is no less important for all that.

In moments of pessimism I begin to suspect that this includes all Greek words. And yet, us latter-day Platonists started off reading Plato in translation, and still managed to fall in love with him, so it cannot be altogether impossible. (Not that we never fall in love with phantoms. Maybe we only ever do.)